All the News That's Fit to Be Paid For? The New York Times and Sustainable Business Models

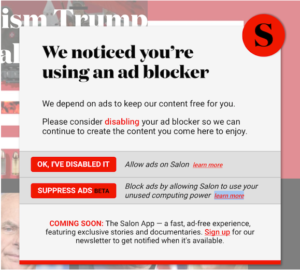

What's it mean to be a publisher these days? Perhaps the New York Times is showing the way into the future, with a looming end to print, expansion into OTT, a wide variety of subscription offerings and a multimedia mindset. Certainly, the Gray Lady is busy evolving its business model in ways that are being copied by other major legacy media companies.And the evolution is certainly in order, given the continued hemorrhaging of viewers and, especially, readers from traditional media to digital alternatives.That reader erosion is so pronounced that New York Times CEO Mark Thompson told investors at a recent conference that the company (and most others) will probably stop making a print product within a decade.Print, of course, was the Times for most of its 167 years. Given the velocity of change, however, it might not take even that long for newsprint to disappear from the Times' otherwise expanding menu of offerings."Without question we make more money on a print subscriber," Thompson told CNBC. "But the point about digital is that we believe we can grow many, many more of them. We've already got more digital than print subscribers. Digital is growing very rapidly. Ultimately, there will be many times the number of digital subscribers compared to print."Though Thompson said the company will continue to offer a print edition as long as it makes sense economically, rising environmental costs, advertiser shifts to digital and tough competition for attention all suggest that sunset is coming soon. As it is, the company added 157,000 digital subscribers last quarter.At the same time, just this week came word of a planned New York Times TV news channel, presumably an over-the-top offering that corrals the company's content into video form. It's a reasonable response to the rapid pivot to video that we've already seen by many online publishers, from Buzzfeed and Vox on down. That pivot hasn't always paid off immediately, as a glut of content has driven down formerly admirable video ad CPMs and resulting revenues.But it's clear that video will be more and more of the future, whether on publishers' home sites or across YouTube, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram and Twitter.Meanwhile, journalism schools, such as at the University of Southern California, where I teach a digital media and entertainment class, are busy collapsing outmoded silos between print, audio, and video. Cross-platform is everything. Journalists of the future may be writing a text component, creating an infographic or motion graphic, building a podcast or cutting a video for their outlet, maybe all in the same day.Most important to watch, to me, has been the Times investment in a wide variety of subscription-based products tucked behind an increasingly sturdy paywall. They include specialty subscription offerings for cooking, health and exercise, even the crossword puzzle. Meanwhile, the past couple of months have seen many other news outlets erect paywalls for the first time, including Wired, CNN and The Atlantic Monthly.Wired's paywall decision was surprising. As a pioneer in online journalism documenting the ebbs and flows of technology and media, it had long resisted paywalls. But it also has been an outlier among Conde Nast's portfolio of high-end magazines. Eventually, building that paywall was probably inevitable.A shift to online subscriptions is being forced as millions of people have begun using ad-blocking technologies on their browsers and mobile devices.Apple now recommends ad blockers in the wake of the Scepter and Meltdown security holes, to prevent third-party malware from being injected through ad scripts. Even Chrome, the most popular web browser, built by Google, which makes the most money from online ads, now auto-blocks highly intrusive ad forms such as persistent popups and autoplay video ads with sound.Ad blockers are an understandable response to the worst impulses of money-starved sites and their advertisers, but they are hurting sites' revenues in a big way. Companies are trying many alternatives, including Salon's experiment with using visitors' CPU cycles to mine cryptocurrency,Facebook also just launched an experiment to help metropolitan newspapers get more subscribers with a paywall project involving 10 to 15 publications. I'm skeptical about Facebook's ability to help anyone but itself (and given its repeated stumbles, even that's in question).But Facebook drives a vast portion of most publications' online views. If this experiment pays off with more subscribers to struggling metro newspapers, hallelujah.Also of note this past week was the announcement of new participants in Scroll, the media equivalent of an OTT skinny bundle. The service, set to launch later this year, will charge $5 a month for ad-free access to numerous news sites, including new additions Business Insider, MSNBC, Slate, Fusion and, yes, the Atlantic. Publishers will keep 70 percent of revenues. Backers include Axel.Springer (which owns Business Insider), News Corp, Gannett and, yes again, the New York Times.I can't guess how Scroll will do, but offering a package of content from big-name sources, at a reasonable price, will be an attractive option to many potential customers.More importantly, media companies are moving beyond the early Internet trope that "information wants to be free." It may indeed want to be free, but people need to eat, including people who gather and transmit information to others. Purely ad-supported content on the web has not proven to be among our best products. One need only look at clickbait sites such as the Daily Mail, or the still-reverberating effects of Russian manipulation of the 2016 election to understand the downsides of a purely ad-driven online economy.In fact, as Google and Facebook try to evolve their sites to prevent such manipulations, it's possible that the best way to protect ourselves from further monkeying is to only read content from sites we're willing to buy directly. That means content through subscription or micropayments or, as Salon is doing with cryptocurrency.Is it possible that, to tweak the New York Times motto, in the future, we'll only care about all the news that's fit to be paid for? My old economics professor used to say, there's no such thing as a free lunch. Someone's paying for it somewhere. By paying directly maybe we can ensure we get only the good stuff, minus the worst the web has to offer to our minds and our culture.

Meanwhile, the past couple of months have seen many other news outlets erect paywalls for the first time, including Wired, CNN and The Atlantic Monthly.Wired's paywall decision was surprising. As a pioneer in online journalism documenting the ebbs and flows of technology and media, it had long resisted paywalls. But it also has been an outlier among Conde Nast's portfolio of high-end magazines. Eventually, building that paywall was probably inevitable.A shift to online subscriptions is being forced as millions of people have begun using ad-blocking technologies on their browsers and mobile devices.Apple now recommends ad blockers in the wake of the Scepter and Meltdown security holes, to prevent third-party malware from being injected through ad scripts. Even Chrome, the most popular web browser, built by Google, which makes the most money from online ads, now auto-blocks highly intrusive ad forms such as persistent popups and autoplay video ads with sound.Ad blockers are an understandable response to the worst impulses of money-starved sites and their advertisers, but they are hurting sites' revenues in a big way. Companies are trying many alternatives, including Salon's experiment with using visitors' CPU cycles to mine cryptocurrency,Facebook also just launched an experiment to help metropolitan newspapers get more subscribers with a paywall project involving 10 to 15 publications. I'm skeptical about Facebook's ability to help anyone but itself (and given its repeated stumbles, even that's in question).But Facebook drives a vast portion of most publications' online views. If this experiment pays off with more subscribers to struggling metro newspapers, hallelujah.Also of note this past week was the announcement of new participants in Scroll, the media equivalent of an OTT skinny bundle. The service, set to launch later this year, will charge $5 a month for ad-free access to numerous news sites, including new additions Business Insider, MSNBC, Slate, Fusion and, yes, the Atlantic. Publishers will keep 70 percent of revenues. Backers include Axel.Springer (which owns Business Insider), News Corp, Gannett and, yes again, the New York Times.I can't guess how Scroll will do, but offering a package of content from big-name sources, at a reasonable price, will be an attractive option to many potential customers.More importantly, media companies are moving beyond the early Internet trope that "information wants to be free." It may indeed want to be free, but people need to eat, including people who gather and transmit information to others. Purely ad-supported content on the web has not proven to be among our best products. One need only look at clickbait sites such as the Daily Mail, or the still-reverberating effects of Russian manipulation of the 2016 election to understand the downsides of a purely ad-driven online economy.In fact, as Google and Facebook try to evolve their sites to prevent such manipulations, it's possible that the best way to protect ourselves from further monkeying is to only read content from sites we're willing to buy directly. That means content through subscription or micropayments or, as Salon is doing with cryptocurrency.Is it possible that, to tweak the New York Times motto, in the future, we'll only care about all the news that's fit to be paid for? My old economics professor used to say, there's no such thing as a free lunch. Someone's paying for it somewhere. By paying directly maybe we can ensure we get only the good stuff, minus the worst the web has to offer to our minds and our culture.