As "Ingrid Goes West," Should Microinfluencer Marketing Go South?

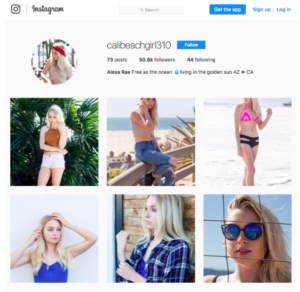

Are we on the edge of another advertiser rebellion? If nothing else, are brands and their agencies about to get more picky about their online ad partners ahead of another potential fraud problem?I don't know if it's going to happen, but a recent sting of sorts targeting microinfluencers, the hottest Instagram marketing trend right now, suggests maybe a little rebellion would be a good thing.The sting comes just as a new movie, Ingrid Goes West, has gone wide, satirizing the vacuous depths of Instagram influencer-driven commerce (See the trailer here).Ingrid won a screenwriting award at this year's Sundance Film Festival, a nod to its timely and pointed take on Instagram stars and their shallow "friendships" with online followings. The dark, occasionally quite funny satire focuses on Ingrid Thorburn (played by Aubrey Plaza) who obsesses about the seemingly perfect life of Taylor Sloane (Elizabeth Olsen), a woman in Venice, Calif., whom she finds and follows on Instagram. Ingrid decides to move west, and insinuates herself into Taylor's real life, with problematic results.The film opened in three theaters Aug. 11 to a strong $45,000 per screen, and expanded (relatively) wide two weekends later, to 647 screens.In the film, Taylor describes herself to Ingrid as a "photographer" who takes pictures on Instagram and sometimes is paid by companies to put photos on there on their behalf. Her following clocks in at 247,000 people.Taylor's "work" affords her a comfortable life: a shabby-chic Venice bungalow, a Mercedes convertible, a getaway house in the desert north of Palm Springs, and a hunky husband whom she's persuaded to quit his job and work as an artist (though in making his first sale, to Ingrid, he doesn't even know what to charge).Taylor, technically speaking, is more than a microinfluencer, but she's hardly a household name. Watching the movie, however, you get an idea of what may be possible for a certain class of influencer (even if the lifestyle is inflated, a la that Friends apartment in Manhattan, for cinematic purposes).But the MediaKix sting I mentioned suggests even small fry, those with as few as 5,000 followers (50,000 is the top end for a typical definition of "microinfluencer"), can score big, even if they're not real people. MediaKix built two Instagram accounts around fake personas, building scale with stock photos and purchased followers, likes and comments.Within two months, after spending about $300 on likes and followers, each account had attracted more than 10,000 followers. MediaKix then signed up the fake accounts for “a wide range of (influencer marketing) platforms.”Through those platforms, each of the accounts – one in fashion and one in travel – snagged a pair of sponsorship deals with big brands, getting free product, cash or both.MediaKix founder and CEO Evan Asano said the company, in a previous study, estimated the Instagram influencer business at $1 billion a year, and is on a pace to double by 2020."Anytime there's money pouring into a new and viable space, there will also be those seeking to exploit these opportunities," Asano said. "We felt that it was important to call this out, so brands are aware and proceed with more diligence and caution. Influencer marketing is growing like crazy and more and more brands are getting involved. In a market worth billions every year, this type of misrepresentation could mean millions of dollars being wasted by brands."Asano acknowledged that, "It's hard to know exactly how common this is. The practice of buying followers and engagement most commonly affects smaller or microinfluencers seeking an easy way to build an initial following and secure paid brand deals. As our experiment demonstrated, this is easy and cheap to do at this level."Instagram remains the fastest growing social-media platform, and it's already huge, at more than 700 million users. And as the market and opportunity grow, so does the sophistication of people trying to game the system."We don't believe a tool, platform, or algorithm exists that can accurately detect and vet fake followers and engagement," Asano said. "If so, Instagram (with their sizable resources and talent) would have successfully eradicated the problem themselves. It's hard to believe that if Instagram/Facebook is unable to adequately remedy this issue that companies of lesser resources and/or talent would be able to provide such a solution."In doing the sting, MediaKix has its own axes to grind, of course. For one thing, it specializes in influencer marketing on YouTube, a significant Instagram competitor. And the company’s blog post describing its sting actually could function as a how-to manual for others hoping to commit the same fraud.But the sting illustrates a real issue for brands and, not incidentally, for legitimate influencers trying to protect the long-term health of their business."It can be harder for larger, more prominent influencers to do this as they tend to be more heavily scrutinized, but there are definitely cases of large influencers who have or continue to buy followers," Asano said. "Because influencer marketing has become such a big business, it fuels this market. So Instagram's growth and the size and growth of influencer marketing makes it susceptible."The answer, for brands and their agencies, is an old one, but it's more true than ever. Know who you're dealing with. As the old Russian proverb invoked by Ronald Reagan put it: "Trust, but verify."

MediaKix built two Instagram accounts around fake personas, building scale with stock photos and purchased followers, likes and comments.Within two months, after spending about $300 on likes and followers, each account had attracted more than 10,000 followers. MediaKix then signed up the fake accounts for “a wide range of (influencer marketing) platforms.”Through those platforms, each of the accounts – one in fashion and one in travel – snagged a pair of sponsorship deals with big brands, getting free product, cash or both.MediaKix founder and CEO Evan Asano said the company, in a previous study, estimated the Instagram influencer business at $1 billion a year, and is on a pace to double by 2020."Anytime there's money pouring into a new and viable space, there will also be those seeking to exploit these opportunities," Asano said. "We felt that it was important to call this out, so brands are aware and proceed with more diligence and caution. Influencer marketing is growing like crazy and more and more brands are getting involved. In a market worth billions every year, this type of misrepresentation could mean millions of dollars being wasted by brands."Asano acknowledged that, "It's hard to know exactly how common this is. The practice of buying followers and engagement most commonly affects smaller or microinfluencers seeking an easy way to build an initial following and secure paid brand deals. As our experiment demonstrated, this is easy and cheap to do at this level."Instagram remains the fastest growing social-media platform, and it's already huge, at more than 700 million users. And as the market and opportunity grow, so does the sophistication of people trying to game the system."We don't believe a tool, platform, or algorithm exists that can accurately detect and vet fake followers and engagement," Asano said. "If so, Instagram (with their sizable resources and talent) would have successfully eradicated the problem themselves. It's hard to believe that if Instagram/Facebook is unable to adequately remedy this issue that companies of lesser resources and/or talent would be able to provide such a solution."In doing the sting, MediaKix has its own axes to grind, of course. For one thing, it specializes in influencer marketing on YouTube, a significant Instagram competitor. And the company’s blog post describing its sting actually could function as a how-to manual for others hoping to commit the same fraud.But the sting illustrates a real issue for brands and, not incidentally, for legitimate influencers trying to protect the long-term health of their business."It can be harder for larger, more prominent influencers to do this as they tend to be more heavily scrutinized, but there are definitely cases of large influencers who have or continue to buy followers," Asano said. "Because influencer marketing has become such a big business, it fuels this market. So Instagram's growth and the size and growth of influencer marketing makes it susceptible."The answer, for brands and their agencies, is an old one, but it's more true than ever. Know who you're dealing with. As the old Russian proverb invoked by Ronald Reagan put it: "Trust, but verify."